Back over on the old blog, when I was a much more serious and consistent writer, and before Tweets and Instagrams and Tik Toks took over the internet, I used to record eerie and inexplicable events which happened in our house just outside Baltimore. Things started to go a bit haywire the final year we lived in there. I called the series Haint That a Shame for some reason which now eludes me, but presumably it was because my maternal grandma had used the word haint once to describe a ghost–I found this twisted form of the word haunt charming as a teen, and it stuck with me.

We moved downtown after ten years in that house and had only a few more strange happenings before things calmed down.

It’s been two and a half years since we bought the old mill in France which we currently inhabit. When the previous owner was showing us around before we bought the place he opened one old room with a skeleton key and referred to it as the chambre des fantômes. We had a brief exchange in French when he said this–I asked him if he’d had any experiences with ghosts and he said he was only joking about the room, which was an old machine shop filled with junk. But, he said, there had been some problems which he’d addressed by having an exorcism done on the building by a shaman (more about that another day).

At the end of February we adopted Bou-Bou, a 2.5 year old French Bulldog. Her previous owner had gotten a promotion at work and was unable to give Bou enough attention, so we bought her and have not once regretted the decision.

Before we met the dog we were told that she was the sweetest, most timid of creatures. When going for walks around town she would meet strangers and immediately roll over and display her stomach to everyone. When we went to visit her a couple times before adopting her, this was our experience–immediately she would shrink down and then flop over on her back with belly and neck displayed. This behavior continued the fist two months she lived with us, and when she was running free around our property she would unfailingly roll over when friends or strangers came by. As we run an hébergement we were quite happy to see this behavior. All spring and summer we have tourists in and out of our rental apartments and we of course wanted a happy dog who turned into a wiggly worm around strangers.

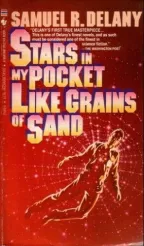

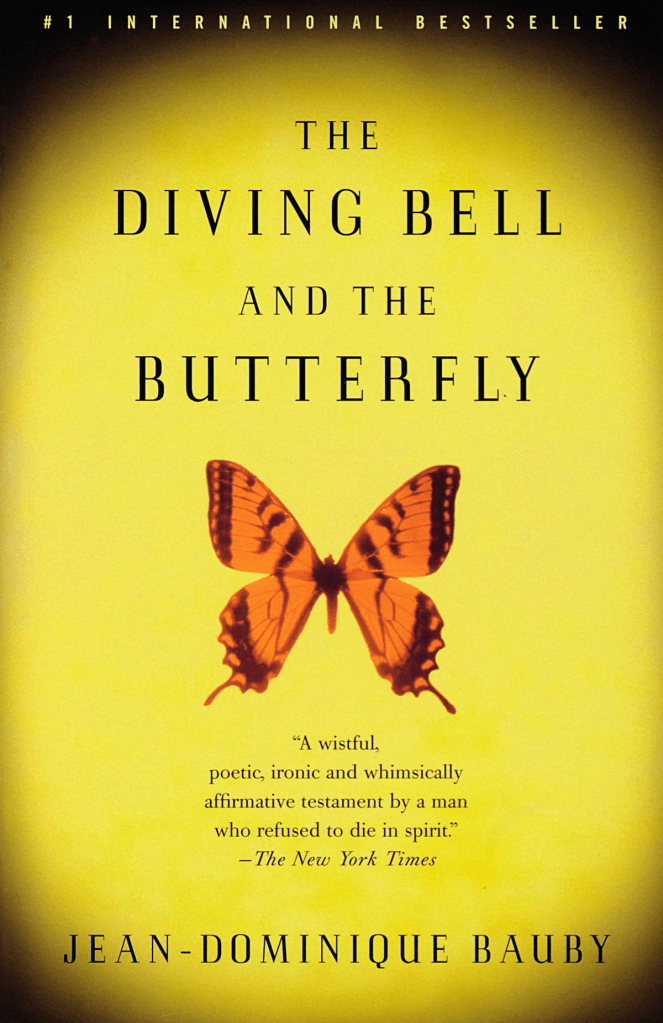

One day when we’d had the dog about two months, my wife went down to the 3rd floor of our building with Bou. That floor is unfinished and used to house several concrete spawning beds for trout. It’s basically an 85-meter-square empty space completely unfinished with some old radiators and debris and a bit of scaffolding off to the side. While my wife was doing some tidying she heard the dog rummaging around and then beginning to chew something. As anyone with a dog knows, you have to immediately check what the dog has in its mouth. Upon close examination, and following careful negotiations with our new pooch, Patricia discerned that Bou had found and started to chew the peculiar button pictured above. Somehow she had found it on the cement floor which had been swept clear earlier.

In French it reads Jamais ne dort–Aboie et mord, which translates in English to Never sleep–bark and bite. Pictured is a fierce-looking French bulldog with an angry red eye. On its collar is the ID number 214e-RR. When I searched this ID and the words french bulldog the top result on Google was a chat stream beginning with this description and a request for more info:

Définition de l’insigne

Le bouledogue régional jamais ne dort, aboie et mord. Dormez donc tranquilles braves Parisiens, les ouvrages d’art et les voies navigables de votre région sont bien gardés… Le réveil sera dur!

Sans nom de fabricant.

Le Colonel GEOFFROY prend le commandement du régiment à la mobilisation

Turns out 214e-RR was a regional regiment of the French army charged with protecting Paris, its art treasures, and its means of transport. Its commander during WW2 was Colonel Geoffroy (the French form of my first name). Nice bit of synchronicity there!

But most interestingly, and quite strangely…the very next day after she found this button and chewed it, Bou’s behavior changed dramatically. She barked at a person walking by, which shocked us as we’d never heard her bark or growl; her hackles were raised and she displayed a terrible fierce aspect wholly opposite to anything we’d seen before. She began charging and leaping at strangers and even friends when they knocked on the door. During tourist season we could no longer allow her to roam free around the property because she would charge ferociously at anyone, even people she’d met several times.

To this day she remains a fierce defender of the Moulin and its grounds and its inhabitants. Even daily visitors get the treatment, and sometimes if I walk into the house suddenly she’ll charge and leap at me! We have to keep her locked on the porch or on a lead now. Somehow the ferocious bulldog spirit of 214-RR has inhabited our little regimental commander and transformed her from a gentle and timid soul to a true and aggressive defender of her territory.