Typically during a debate or argument I maintain my cool, and rarely get emotional even when provoked by claims I find distasteful or offensive. But last Thursday at dinner with friends I totally went off the rails during a debate about covid and vaccines and mask requirements. Perhaps it was the full Blue Super Moon pulling tides in my brain and causing me to lose it and show my exasperation? Whatever the cause, I regretted my display–which included repeated interruptions and a contemptuous tone and several loud “that’s not true” interjections. This behavior was disrespectful and atypical of how I usually handle such situations: listen quietly, seek to understand, and respond out of interest and love.

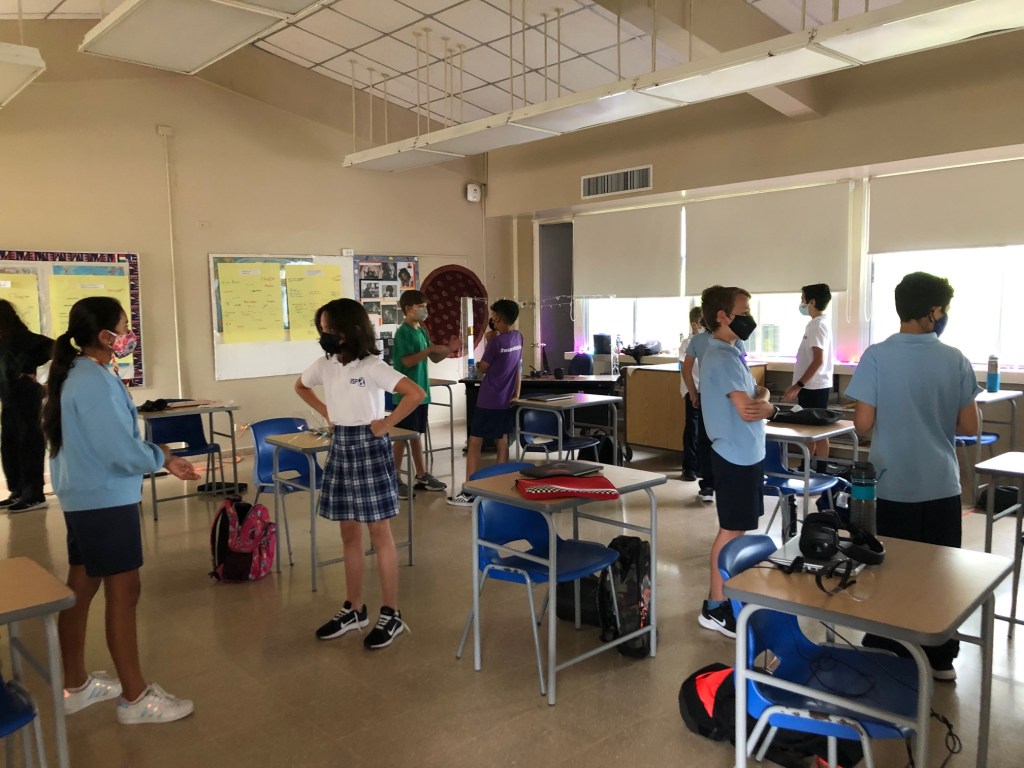

I was arguing that mask mandates and stay-at-home orders were perfectly understandable given the circumstances. Even ancient civilizations knew that when the pestilence came around it was best stay indoors until it passed. In retrospect we can see that some covid restrictions were too severe and perhaps even ridiculous (I had to sit behind a thick plexiglass wall at a desk while masked, for example, with a classroom of masked students present and the other half at home on the internet–definitely overkill). As for vaccines, I was all for them, and the idea that vaccines based on more than 40 years of laboratory research were “rushed” and were killing more people than the disease set me off. And when one friend suggested that covid was a hoax and not really serious and that hospitals were never overrun I went into the stratosphere. I heard a lot of “they’re saying” and “they know” arguments to which I kept responding “WHO, WHO says, WHO knows?” The evidence almost always was a slickly produced YouTube video, or a politician referring to one.

A friend said “I’m surprised you of all people would take the side of government agencies and defend Big Pharma.” This was a good angle of attack, and hit hard. But like Noam Chomsky, I see that there is a move underfoot by oligarchs and major corporations to undermine trust in public institutions because these are the only remaining restraint on the power of super-wealthy amoral elites whose avarice and contempt for law and ethics is having profound and perhaps irreversible impacts on not only the social fabric but perhaps the survival of humanity as a species. And like Chomsky, I know that even a long time skeptic and critic of government can realize that public agencies at least somewhat responsive to the will of the masses are the only brake we have on the continued destruction of Earth for profit. Yes, agencies like the FDA and CDC have been corrupted by Big Pharma and Big Insurance, but this is a simple tweak to fix by law. If the corruption comes from corporations, why blame the government agencies? Instead blame those who pull the levers and clean up the agencies with regulations about conflict of interest and ethics requirements.

Do I share skepticism of gigantic corporations like Pfizer and Moderna making billions of dollars from mandated vaccines? Of course I do. I don’t think medicines or health care should be for profit at all. I also respect suspicions that the vaccine was rushed, and particularly understand the reluctance of many people of color to get the vaccine given the long and sordid history of medical “experimentation” and abuse by authorities. But there is a great deal of wholesale quackery disseminated on the internet–remember how vaccines would magnetize your blood and make keys stick to your body? And a lot of the goofiness is given a veneer of scientific respectability by doctors who create videos on YouTube and get click/view money for saying unproven outrageous things to scare people to death (so they rush out and buy herbal supplements to counteract mythical side effects).

But I think a more important and often ignored moral and ethical question is why do these companies get all their R&D and testing paid for by public money and then they get to take government funded drugs and vaccines, patent them, make enormous profits from them while paying executives and stockholders huge dividends, while in turn they don’t even pay taxes. THAT is the real problem, and Big Pharma is certainly content to have people debating whether or not Dr. Fauci is a lizard being from the Pleiades or whether sheep medicine is a valid treatment instead of “why is the system rigged this way?”

All of this is my roundabout introduction to having seen the Oppenheimer film. I thought it was a strong attempt to address a lot of the concerns raised in our discussion last Thursday about science and ethics and who decides what is right or wrong, etc. Should we get vaccines during a raging pandemic because scientists and government officials say so? Or, more in line with the themes of the film: Should we detonate a device which the government wants but which has a close to zero chance of igniting the atmosphere of the entire Earth?

Oppenheimer was of course a brilliant scientist, but he was also steeped in the humanities and was well-aware of the ethical considerations complicating his work on the Manhattan Project. The continual butchery on two fronts during World War II, the likelihood that Nazi scientists were themselves close to the bomb and could give Hitler an unspeakable weapon, the ongoing Holocaust–all of this provided enormous impetus to successfully construct a nuclear bomb and test it first. But Oppenheimer was also a literary-minded guy who’d read his John Donne and Bhagavad Gita. He was also a socialist flirting with communism and had profound doubts about what might become of the United States if it had this ultimate weapon. These doubts were of course later shared by President Eisenhower as he left office. And the film makes it clear that the second use of the bomb in Oppenheimer’s opinion was unnecessary overkill and was even more likely than the first to provoke a disastrous arms race–which proved correct. (Of course Paul Fussell would disagree that the 2nd bomb should not have been dropped on Japan.)

Oppenheimer is a massive film and will sap all your energies, but if you like dense character studies full of moral ambiguity and difficult ethical questions, you will dig it. In its scale and tone it’s reminiscent of Scorsese’s long films with their questions about ethics and violence (think Taxi Driver, or The Silence, or Raging Bull, or even Bringing Out the Dead). I think all the performances were excellent, and appreciated the use of a brief interaction between Einstein and Oppenheimer as a bookend to the plot. This is clearly Christopher Nolan taking his best shot at a Best Picture nod, and he might pull it off. There are of course problems with the film–after the excitement of the bomb build-up, it’s difficult to reset and endure the political persecution of Oppenheimer by right-wingers and professional rivals which goes on for another hour. But this part of the story also must be told. And yes, because everything else is thrown in, Nolan should have at least mentioned or shown what happened to the residents of New Mexico, largely Latino and Native American, before and after the tests, and though the horrors unleashed on Japanese civilians are suggested in a kind of panic attack hallucinatory sequence, I’m not sure it’s an adequate portrayal particularly given the thematic concerns of the film and its focus on the dilemmas navigated by Oppenheimer, et al.

One of my dinner conversation adversaries pointed out that we might not know the answers to many of our questions about covid and vaccines for many years. And, just like the atom bomb, Pandora’s Box has been opened and we live with the consequences.

Side note: nice to see Robert Downey Jr without a goofy super her0 costume!

Another side note: Twin Peaks The Return Episode 8 is still the pre-eminent cinematic exploration of the ethical questions around the explosion of the first bomb. In the Twin Peaks universe the explosion results in the birth of Bob, a demonic character who causes some chaos in the small town. Bob–Robert Oppenheimer? Or Bomb? Or, Bob’s Big Boy?

A further side note: I’ve recently been re-reading books which had a profound impact on me as a young person. One of these is a volume of science fiction stories edited by Harlan Ellison called Again, Dangerous Visions. I’d just read two stories in the volume which were not sci-fi, but rather fiction with science involved. These were by Bernard Wolfe. One was about a woman who takes her poofy expensive pure-bred dog to witness a test of napalm at a local military base. Her dog gets immolated in the test, which is so sad and terrifying for her and the other witnesses who fail to make the leap that this stuff will be dropped on actual human beings elsewhere. The other was about sleep experiments gone awry. But at any rate Wolfe’s accompanying essay excoriates sci-fi authors and the scientists they idolize. Further, he damns US-style hyper- capitalism and its “fawning upon scientists” while exploiting them and “their fake charisma.” He thought scientists exploited by capitalists were set to unleash profound and unforseable horrors on the world, and bemoaned the privileging of science over the humanities. Like Colin Wilson used to say, the “library faeries” will drop the reading material you need in your lap when you need it.