Back when I was young and energetic I spent a couple decades working a full-time job, a part-time job, and going to university full-time. At some point in this burst of insanity I was working in the Cook Library at Towson University, while teaching in the English Department, and still working at Borders Books & Music, while pursuing a degree in French Literature and also taking courses necessary to become a public school teacher. At that time I’d already earned a Bachelor’s Degree and a Master’s Degree–but it was never enough, LOL.

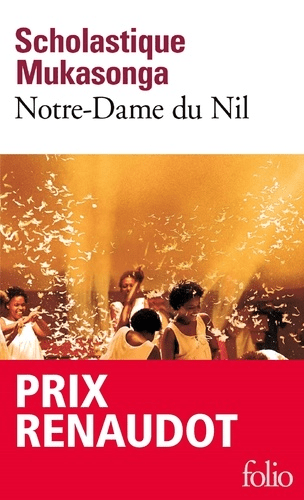

During that burst I took a really brilliant class with Dr. Lena Ampadu focused on literature in English coming out of post-colonial Africa, and also took a delicious class in French with Dr. Katia Sainson focused on postcolonial lit. So a couple decades later when an algorithm suggested Notre Dame du Nil on sale I purchased it while living in an oceanside apartment in a high-rise in Panama. I desperately wanted to improve my Spanish but also wanted to keep my French alive. Six years later I finally got around to reading it.

It was worth the wait. Ostensibly a memoir novel set in an all-girl’s school in Rwanda in the early 1970s, it is actually a densely layered critique of colonialism. Imagine Mean Girls if Franz Fanon dropped in as script advisor.

The French was not too difficult, and I needed to consult a dictionary only a few times each chapter. The characters are engaging and I found much of the novel quite interesting and at times hilarious. The girls at Notre Dame du Nil are all Rwandans who are being groomed for elite roles–they are daughters of wealthy merchant families, of diplomats, of government figures or military officers. Many come from small rural villages and of course “elite” grooming requires the learning of European languages, European traditions, European religion, European manners…The Europeans teaching in the school are hapless and ridiculous and deserve the mocking they receive. The Catholics in charge of the institution are just as bad. The school has as its setting one of the furthest away sources of the Nile river, hence the designation in the title. The bits about Rwandan culture, including a fascinating sequence when two students visit a rain-making shaman to purchase a love spell-were excellent. And the fishy Catholic priest in charge of the school who bestows nice garments on girls but only if they try them on in front of him? Classic.

One tangent of the plot involves a European man who lives on an old coffee plantation and has a bizarre theory that Tutsis are descended from Pharoahs–he abducts a student and then begins painting her and using her in a film he’s making. Another involves a visit to campus by the Queen of Belgium.

But the novel slowly simmers and builds a truly dark and disturbing undercurrent as the typical mean teen girl drama reveals roots deeply entwined in Hutu and Tutsi history, with absolutely catastrophic results. What at first seems like surly teen sniping eventually develops an undercurrent of tribal hatreds and it becomes clear that the parents of several students are encouraging the cataclysmic outcome. “It’s not lies, it’s politics,” says a ringleader who happens to be the daughter of the President of Rwanda. One student, who is half Tutsi and half Hutu, does her best to straddle two worlds and attempts to insinuate herself into the dominant group but redeems herself to a degree when the crisis comes.I shan’t say more to avoid spoilers.