The town where I grew up in the 1970s was still, in many ways, actually in the 1950s. In Stewartstown, PA The Beatles were long-haired hippy freaks who hated Jesus, anyone to the left of Barry Goldwater was a Communist, and guys still hung out in their denim overalls by a potbelly stove in the feed store. My grandfather, who was almost totally bald, walked two blocks to the barber’s to get his “ears lowered” and hung out with the gents there for a couple hours. Our neighbor one house south of us on Main St was Mrs. Hersey.

Mrs. Hersey wore dark blue or black dresses which covered all the way to her neck, to her wrists, and to her ankles. The dresses were finely made and very austere, but there was elaborate white lace at the neck and on the sleeves. She also covered her hair in the traditional manner of churchwomen in that region at the time when she was outside or when she was hosting company. She would summon me to the fence between our yards when I was four or five years old. “Master Godfrey how do you fare today?” She always referred to me as “Master” followed by my last name, and addressed Christmas cards to me in the same manner (I think I still have one of those). After a bit of conversation she would hand me a small paper bag of chestnuts.

Mrs. Hersey didn’t have a living room like everyone else, she had a parlor. But the parlor to my at the time little mind just seemed like an old-timey living room. There were glass oil lamps with globes and wicks which had been converted to electric lamps. The glass was infused with different colors like mauve or mint green, often swirled with white foamy glass and sparkle flakes. Her parlor reminded me of the interiors in old western movies. There were doilies under everything: hard candy dish full of root beer barrels, the lamps, family pictures. And every table was covered with a cloth to boot, as were the chairs, which also had lace at the top and on the arms.

In Stewartstown I had the freedom to go anywhere unsupervised, and my friends and I did so. Favorite haunt was the old town cemetery directly behind our house, but we roamed widely and often for hours at a time without adults or elder siblings. We had this freedom because of the old ladies in town, who knew everyone and everyone’s brood and everyone’s business. From their front porches and from chairs hidden behind front window curtains they somehow divined all the latest gossip. But the old ladies kept an eye on us, took us in when we tumbled by on the sidewalk, came out with Band-Aids when someone fell, and in certain circumstances might deliver a stern lecture, a warning to call our moms, and occasionally, dealt us a smack.

I used to love visiting with the old ladies. They were all born around the turn of the 20th century and had seen so much–imagine they’d all had horses and horse carts when they were teenagers? They told wonderful stories and told me about my grandparents and father when they were all young people. When my parents got divorced and my mom and sister and I moved in with my maternal grandparents in a different small Pennsylvania town, I continued the tradition of visiting old ladies. My grandma would give me a sack of veggies from her garden and say “Take this up to old Mrs. Kent and tell her $1.20 please.” I’d tie the plastic bag to my bike handlebars and ride off. Mrs. Kent had more hair on her chin than on top of her head, and wore simple house dresses with a full body apron as she sat in her rocker and told me about the photos on her tables, or about her knick-knacks, or about that one time she got a train to Baltimore, or about her long-gone husband. Then she’d give me some shoefly pie and $1.20 in coins to take back with me.

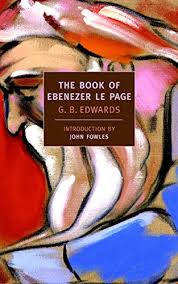

All of this as prologue to show I’ve often delighted in the company of old people, and truly treasure my opportunities to do so when I was a very young lad. And this novel by G. B. Edwards reminded me so much of my visits with old folk back in the 1970s and early 1980s that I felt a profound nostalgia, despite never having been to Guernsey Island.

The Book of Ebenezer Le Page came to my attention recently as I was scanning my bookshelves and planning future reads. I’d read a couple articles lately about Guernsey Island and some controversies about its time under German occupation and what exactly happened in the labor camps there. I picked it up to read as a secondary novel (I typically have a primary novel and a secondary going at the same time (and also a primary non-fiction and fiction going at the same time (and routinely a primary novel in French as well))) and with regular 6-8 page chapters finished it off in a couple months.

What a pleasant and interesting old chap Ebenezer Le Page turned out to be. And what a lens through which to see the changes in an island culture over the early 2/3rds of the 20th century. Ebenezer of course is not an old man throughout the novel, but the novel is told by old Ebenezer who is writing his memoirs. If you are a fan of plot and excitement, this is not a novel for you. If you like to visit old folk and set a piece and hear what they have to say–you may well enjoy this book. I particularly enjoyed Ebenezer’s run-ins with Liza and actually laughed out loud reading them. But we get his entire life story and his interactions with friends and family as the island where he lives moves from the 19th century and into the 20th and through the world wars.

Surprisingly, there are gay characters in the book and it’s interesting to note Ebenezer’s mindset and reactions to them. And Ebenezer remembers some details of the Nazi occupation of Guernsey which continue to be controversial. I particularly enjoyed learning about the patois of the island with its mixture of French and English cultures and languages. There is a useful dictionary in the back!

I was genuinely sad to reach the end of this novel–that rarely happens in life, even when you read a lot of great stuff.